Embroiders with a golden touch

Hand-sewn embroidery stitched with golden and silver thread — jinyin caixiu — is a national intangible heritage in the city of Ningbo. Compared to its counterparts in other provinces, it features more ornate patterns and auspicious themes by using bright-hued thread and brocade.

Its history could date back to the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279) when ancient craftsmen sewed jinyin caixiu on costumes, ritual objects, and wedding and birthday ceremony ornaments.

Piece of embroidery created by Xu Jinlun

The shifted economic center accelerated its development after the royal court made Hangzhou the capital in present-day Zhejiang Province during that dynasty. Meanwhile, majestic Buddhist etiquette and ceremonies augmented the demand for embroidered canopies, prayer flags, robes, curtains and draperies.

Ningbo was dotted with temples with hundreds and thousands of devout believers, as Buddhism had prevailed in the city since the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907). Some ancient religious venues, including Tiantong and Xuedou temples, are still flourishing with incense burners today.

In addition, Buddhist paintings sewn with jinyin caixiu spread to Japan and Korean Peninsula at the time. That market demand was expanded further.

Opera also prospered in Ningbo, where theaters and teahouses were always alive with folk music. Ornately designed costumes stitched with mythical creatures and floral patterns were the biggest feature of Zhejiang operas.

By virtue of abundant silk production and a thriving seaborne trade, plus the promotion from religion and operas, jinyin caixiu quickly grew into a pillar industry during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

Authentic jinyin caixiu features a dozen stitching types, sharing some similarities with counterparts across the country, but distinguished by outlines with gold and silver thread.

In ancient times, costumes and ornaments for the imperial family were embroidered with real gold and silver — metal was ground into a thin layer and then cut into strings, and then intertwined with cotton into thread.

The ornate style was popular with ordinary people. They used golden and silver-colored thread instead of precious metals and then applied the stitching techniques in their clothes.

In its heyday, almost every household in Ningbo sewed embroidery, and women were expected to be skilled in needlework from an early age. One of the standards of judging a good wife, or fine lady, was her skills in embroidery.

A piece of embroidery created by Xu Jinlun

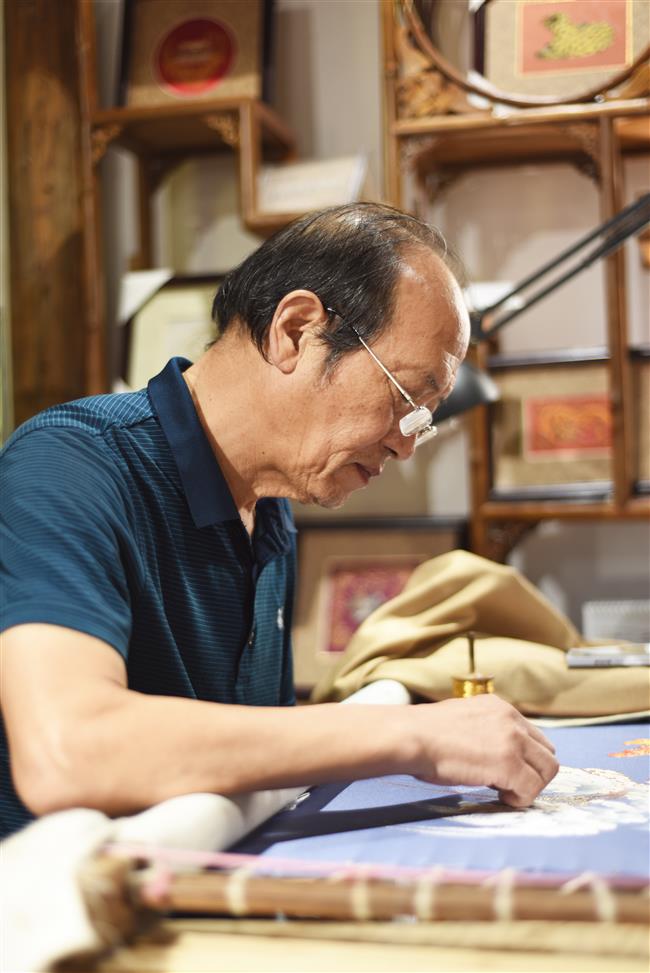

Xu Jinlun, 71, is an exception in this feminine tradition. He was sent to state-owned Ningbo Embroidery Factory to learn the skills at the age of 14. Being the seventh generation of a prestigious embroidery family, it was hoped he would carry on the family’s heritage.

“Embroidery requires years of practice. After the first year of training, I could only sew the simplest floral patterns,” Xu said. “My father told me to penetrate a dot on brocade with a needle for weeks, aiming to strengthen finger power and hold a needle more steadily.”

Xu showed a lot of talent at the beginning. By virtue of his prominent expertise, he took charge of the design department in the factory that then had more than 300 expert embroiderers.

Xu Jinlun sews a piece of embroidery.

In the late 1980s, he designed a piece of work and sewed with six co-workers for a year. The embroidery was stitched with 100 cranes flying over the sea and well-known landscapes over the country. It was included as a national-level treasure in 1989.

The factory also exported a large number of embroidery pieces overseas, since Oriental-style needlework had found favor with Europeans and Southeast Asians. The large demand boosted the development of the industry. The factory had to dispatch orders to folk embroiderers all over Ningbo.

“At its peak, there were more than 50,000 embroiderers across Ningbo,” Xu recalled. “Today, only two dozen still persevere with embroidery.”

Machines gradually replaced people, as the former could save cost and labor. Hand-sewn versions were no longer popular in the market because of the high price and time consuming. The craftsmanship declined year by year. In 2009, the factory shut down and most embroiderers changed to other industries.

“The closure severely beat jinyin caixiu. Besides, the young generation is no more into traditional embroidery,” added Xu. “Fostering talent takes many years and old craftsmen are losing the techniques due to blurred vision and shaky hands.”

Xu has three apprentices and his children are also learning how to sew. However, he’s worrying about the future.

Shi Cuizhen (left) and Sha Jinzhu work together on a piece of embroidery.

“Embroidery requires patience and perseverance. Young people often lack the two characters,” Xu said. “They prefer fast fashion rather than traditional crafts. Actually, they think embroidery outdated.”

A few years ago, Xu was given the title of a national-level intangible heritage craftsman. Today, he has been invited to work in Yinzhou District Intangible Protection Center in Ningbo along with two embroiderers, 69-year-old Shi Cuizhen and 70-year-old Sha Jinzhu.

Now, the three embroiders on site, showcasing their techniques to visitors. Shi and Sha are also responsible for teaching students from local elementary and middle schools, aiming to raise inheritors carrying down the craft.

Sha showcased a piece of work from a pupil. Though the needlework is crooked, it still looks better than embroidery from other beginners.

“Some kids show great interest and talent. Happily for us, local schools often organize visits to our center, letting students get to know about embroidery,” Sha adds.

In order to expand market demand and attract more youngsters, local embroiderers have started to integrate the craft with creative industries. Qiu Qunzhu, who has been devoted to the craftsmanship for decades, established the Ningbo Jinyin Caixiu Co with an investment of 28 million yuan (US$4 million) in 2011.

Xu Jinlun’s stitching

Apart from displaying collected antiques made in the late Qing Dynasty and Republic of China (1912-1949), the company has invited a batch of craftsmen and designers to produce creative products in line with market demand.

Vintage embroidery is revived on innovatively designed accessories, knickknacks, ornaments, purses and dresses. Conventional embroidered objects are revitalized after being injected with modern features.

“We focus on practicality when designing daily necessaries in order to cater for the market, and emphasize precious materials when making crafts to highlight artistic and collection value,” said Xu Benfei, a young designer who joined the company in 2013.

Buddhism objects including canopies, prayer flags, robes, curtains and draperies are among the company’s most popular products. Every year, temples and devout Buddhists across the country will order hand-sewn embroidered products.

A handbag with the embroidery from Ningbo Jinyin Caixiu Co

In addition, the company offers ready-to-wear and custom-tailored costumes for ceremonies and events. Among them, wedding dress is the most popular. Qing Dynasty-style red wedding gown sewn with phoenix motifs, or xiuhefu (秀禾服), is worn by bride for traditional wedding ceremony.

However, a handmade version is pricey because of the time-consuming needlework. Now, the company provides a rental service, allowing people to wear the splendid dress but at a low price.

Commercial development is not the only goal for Qiu. Her company has launched an experience course that welcomes people to learn embroidery. They just need pay 30 yuan for materials, and then can learn sewing techniques from veteran embroiders for free.